Coffin, Charles Coffin. Stories of Our Soldiers. War Reminiscences, by “Carleton” and by Soldiers of New England. Collected from the Series Written Especially for the Boston Journal. Ed. Charles Coffin Coffin. Vol. 2. Boston: The (Boston) Journal Company, 1898. p. 193-203 Link to book on Google

FIRST TROOPS IN RICHMOND.

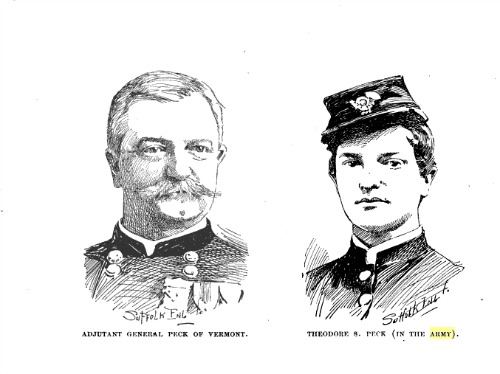

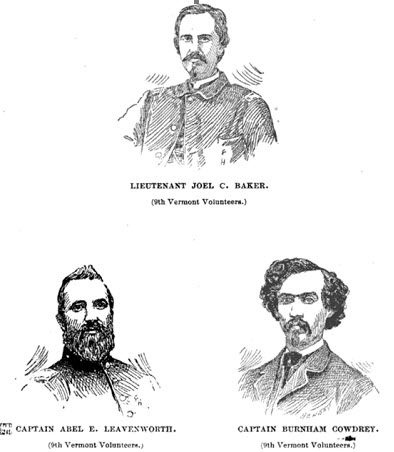

In the Journal of December 10, 1892, was published an article headed, “First Troops into Richmond,” and written by First Lieutenant Royal B. Prescott, Company C, Thirteenth Regiment, New Hampshire Volunteers. On the 12th of January, 1893, and article appeared headed, “First Union Troops in Richmond,” by Capt. Wm. M. Kelley, Tenth New Hampshire Volunteers; and on the 21st of January, 1893, another article appeared headed, “Richmond Once More,” signed by Lieut. Prescott. These communications were forwarded to Hon. Abel E. Leavenworth, Professor of the Vermont State Normal School, Castleton, Vt., late Captain Company K, Ninth Vermont Volunteers; Hon. Joel C. Baker, a leading lawyer of the Vermont Bar, Rutland, Vt., formerly First Lieutenant Company K, Ninth Vermont Volunteers, and Burnham Cowdrey, Captain Company D, Ninth Vermont Volunteers (at the time of this action Second Lieutenant Company G), Bradford, Vermont.

I send the reports of these officers, also their photographs taken during the war. Prof. Leavenworth and Capt. Cowdrey are both invalids, suffering from exposure during the War of the Rebellion, which is my excuse for the delay in replying to the statements of Lieutenant Prescott and Captain Kelley.

The Tenth and Thirteenth New Hampshire Regiments served in the same brigade and division with the Ninth Vermont, of which I was a member, and I take this occasion to say that there were no braver men or better officers in the Union army. I believe that all correspondence between soldiers fighting for the same cause should be friendly and with the best of feeling, and this is given in no other way.

THEODORE S. PECK,

Adjutant General.

Rutland, Feb. 11, 1893.

Gen. Theodore S. Peck, Adjutant and Inspector General of Vermont:

Sir—In complying with your request for a report of the operations of the picket line in front of Richmond, with which I had an humble part, on the morning of the 3d of April, 1865, I have to rely upon my memory. I shall not cite newspaper correspondents, either contemporaneous or of a later date. Indeed, I believe it was generally claimed by the knights of the quill at that time that the colored troops of the Twenty-fifth Corps were the first Union soldiers to enter Richmond. This claim was equally erroneous with the later assertions of many brave officers and honorable men that they were the first to enter the Capitol city of the Confederacy on the morning when it was thrown open to visitors from the Union army.

After the rearrangement of the Confederate defences of their Capitol, upon the capture of Fort Harrison in September, 1864, the line was run nearer the river than formerly, so that their largest and strongest work in the outer line of defences, Fort Gilmer, was within about four miles of the city limits. From this the line trended toward the east and bore away farther from the city, so that Gilmer became the nearest point, and before the Charles City road was reached the works erected to repel McClellan in 1862 were in the outer line of defences. The picket line held by Second Brigade of the Third Division of the Twenty-fourth Corps was directly in front of Fort Gilmer and not farther [194] than 250 yards from it. The pickets of the First Brigade were on the right of the Second Brigade, and as they conformed somewhat to the trend of the Confederate line, were at a greater distance from Richmond than those of the Second Brigade. The Osborne turnpike ran nearly parallel with the river from the vicinity of Dutch Gap to Richmond. The Newmarket road united with the turnpike some two and one-half miles below Rockets, the Richmond steamboat landing. The Darbytown road, the Charles City road, and the Williamsburg road, all united with the Osborne turnpike at or just outside of Rockets, so that by coming by any of the roads between the James River and the York River Railroad, the entry to the city was made at substantially the same point.

Sunday, April 2. 1865, was full of excitement and expectation on the picket line in front of of Richmond. The dull thunder of cannon reached us from the south, by which we knew that Grant was at work below Petersburg. Staff officers from the headquarters of Weitzel and of Devens visited us frequently, scanned with their glasses the line of the enemy from Fort Johnson as far as it could be seen, and gazed wistfully at the steeples of Richmond that stood before as in the bright sunlight. Each visitor brought us fresh installments of such news as is current in a military camp, where the expressed wish of one man becomes an accomplished fact by the repetition of a few moments. The rebels also showed unusual bustle and activity. We could see them leveling glasses in our direction, and details were using strenuous efforts to strengthen their works, especially at Fort Johnson and northerly toward Fort Gilmer The day closed with the utmost activity and watchfulness on both sides.

Soon after dark the First Brigade of the Third Division of the Twenty fourth Corps, commanded by Brevet Brigadier General Edward H. Ripley, marched out and went into bivouac immediately in rear of the picket line of that brigade.

A short time after this Captain Bruce of General Devens’s staff accompanied an engineer officer of the Twenty-fifth Corps to our line and laid out an earthwork on a slight eminence to cover cannon, to be used as a prelude to an assault to be made by Ripley at daybreak, and I was directed to give certain orders to the officer to be sent out with a detail to build the work contemplated. Those orders were not delivered, as no detail came. The night was intensely dark, and no light was allowed on either side. The fires at the reserve were not lighted, and even the Confederate camps were thick with unbroken darkness. The rebel videttes had refused to talk all day, and when night came we were equally silent. The silence was oppressive as the night wore on. At a little past 1 o’clock we secured our first and only deserter on our part of the line that night. He was an intelligent young fellow, and told us that the picket line in our front had been withdrawn and ordered back to camp, and that he believed it meant an abandonment of Virginia, and as a Virginia man he deserted to save being compelled to leave his State when the Confederate army withdrew and left it to fall under the control of the Federal power.

We sent this man to Gen. Devens’s headquarters and continued our watch. About two o’clock there shot up from Fort Johnson on our left a bright column of flame, resembling that of a burning tar barrel. This signal flame burned perhaps three minutes, and when it died out our ears were greeted with the rumble of wagons and ordnance, and the tramp of marching men as the division of Gen. G. W. C Lee of Ewell’s corps moved off to the pontoon bridge and across the James, never to return.

At the first streak of dawn, Capt. Bruce and Lieut. Col. Bamberger of the Fifth Maryland, the division officer of the day, appeared and ordered the picket line forward.

We moved forward to the thick line of abattis in front of the rebel works, then filed through the works and deployed on the other side. The gray light of the early dawn was not sufficient to allow us to see objects at a moderate distance, and it was not until we had deployed on the Richmond side of the rebel works that we found that only a section of the Second Brigade picket had advanced. As I now remember it we had men from only three regiments with us, namely: Ninth Vermont, Twelfth New Hampshire and Fifth Maryland. As we formed inside the works and moved forward, Col. Bamberger rode back to bring forward the remainder of the picket line, and we must have been on the way to Richmond nearly 30 minutes before the pickets of the First Brigade and a considerable proportion of those of the Second Brigade received their orders to move.

Our line advanced rapidly as skirmishers for a few rods, then rallied on the road, which I understand was the Osborne turnpike, and went forward at double quick the entire distance to the city.

Many of our men were exhausted and fell out by the way, so that when we reached the city not more than half the men who started on the advance from Fort Gilmer were in hand. Only five officers were there at the halt—Capt. Sargent. Twelfth New Hampshire; Capt. Leavenworth. Ninth Vermont; Lieuts. J. C. Baker and Burnham Cowdry. Ninth Vermont and a First Lieutenant of the Twelfth New Hampshire, whose name I am unable to recall. This force entered the city and marched to Church Hill, where we fell upon the ground and rested for a few moments. While we were there a few staff officers rode past. Some of them I knew at the time, but can now recall but two of them, Majors Stevens and Graves of Gen. Weitzel’s staff. We fell in and followed these officers into the burning streets, lying between us and Capitol Square. Before we reached the City Hall, we were by some one directed to proceed to Jefferson Davis’s house and await orders.

This we did, and remained about half an hour, when we received orders to station guards on near streets, to stop plunderers who were carrying away stolen property. This took all our men, so that we felt we had received further orders and were not required to remain at the house of the Confederate President any longer. [195]

[196] Soon after we left the Davis house another detachment of Onion troops appeared there and remained for a considerable time. This force I understood to be a part of our picket line that was ordered forward by Col. Bamberger, after he had seen us well on our way.

I have carefully read the newspaper articles of Lieut. Royal B. Prescott and Cape. Warren Kelley with much interest, and should believe the account of either of them were it not for the statement of the other and the facts that I can recall within my own knowledge. Either of the accomplished officers named would have been perfectly competent to lead the advance, and doubtless each thinks that he had that honor, but the error of each is that he did not know what was ahead of him.

The fact that Lieutenant Prescott was joined near Richmond by Lieutenant David S. Keener, Fifth Maryland, and his squad of exhausted men, seemed potent proof that Prescott was not ahead, as stragglers and exhausted men always fall into the rear and never proceed in advance of the command to which they belong. Lieutenant Keener was without doubt a part of the line first over the works, and started with us on the race to Richmond, but he was not with us when we reached there. He fell behind with the men whose endurance failed, and was picked up by Lieutenant Prescott’s detachment, which followed about 30 minutes behind us.

Unless my memory is wholly at fault, Lieut. Prescott is mistaken about the distance the second brigade pickets had to march, it is less than five miles instead of more than seven miles from our picket line in front of Fort Gilmer to Richmond, and that was the nearest point by any road to the city. The detachment that started first was in the advance and it kept it, so that the balance of the picket line did not come in sight of it, except the exhausted men who had fallen out, and were overtaken just outside the city. I say overtaken, because it does not occur to me that the exhausted men would outrun and overtake the vigorous command, well in hand, pushing forward to take possession of a surrendered city.

Capt. Kelley may have been ahead or behind Lieut. Prescott, and I have no means of knowing which one reached Richmond first, as I did not see Prescott’s command at all, and only saw Kelley’s force at “Jeff” Davis’s house after we left it.

Later in the morning I witnessed the triumphal entry into the city of Ripley’s brigade. It was a stirring scene. Three full military bands were playing patriotic airs at the head of column. The step was exact; arms at right shoulder and distances kept with the precision of a parade drill. The Thirteenth New Hampshire was the leading regiment in the column. Gen. Weitzel gave the charge of military affairs to Ripley, and a few moments sufficed to direct the troops to the work of saving the city from the devouring lire that for hours had been sweeping to destruction the business part of the proud capital of the Old Dominion, and the hotbed of Confederate official life.

General Devens was accustomed to say that the first organized body of troops to enter Richmond that morning was the Thirteenth New Hampshire. This was true in the sense that an organized body must have and be with its colors. A picket line is a body of officers and soldiers on special duty and has no colors. It therefore, does not come within the military definition of an organized troop, but Devens often spoke of the pickets of the Ninth Vermont and Twelfth New Hampshire being the first soldiers to reach the city.

When the First Brigade pickets moved forward General Ripley insists that his brigade followed them right forward and kept them as an advance guard until he reached the city and his command did not at any time come in sight of the first detachment. The Confederate flag at “Jeff” Davis’s house was there upon our arrival and was taken away by myself. This is the only thing I know of having been taken from that mansion before Captain Kelley arrived, although there was time enough after we left the house to have stolen a ton of silver plate, if it had been there, before Kelley arrived in sight.

Captain Abel E. Leavenworth and Lieutenant Burnham Cowdry are yet alive and can corroborate the substance of this report. Captain Sargent and his Lieutenants have not been kept in view by me and I do not know whether they are alive or not. Very respectfully,

(Signed) JOEL C. BAKER,

Late First Lieutenant Company K, Ninth Vermont Volunteers.

CAPTAIN COWDREY’S STORY.

General T. S. Peck. Adjutant and Inspector General, State of Vermont:

Dear Sir—After the reorganization of the Army of the James early in December, 1864, the Third Division of the Twenty-fourth Army Corps furnished men for picket duty in that neighborhood until the capture of Richmond, Aprils, 1865. The night of April 2 I was on picket duty at the right of Fort Harrison, and near a road which ran westerly into the city, and which was about a fourth of a mile from the river, as near as I could judge. Some call this road the Osborne Turnpike, but I do not know its name. It ran through the rebel works into the city. I was then a Lieutenant of Company G of the Ninth Vermont Regiment.

This portion of the picket line was guarded by pickets from the Second Brigade of the Third Division, and had been so guarded since September. On the night above named, Captain Abel E. Leavenworth, Lieutenant Joel C. Baker and myself, all from the Ninth Vermont Regiment, were on duty and in command on that portion of the picket line. We had received special instructions to be on the watch for any indications of evacuation on the part of [196] the enemy. About 11 o’clock we heard the sounds of the movement of wagon trains in the rebel lines, and sent word to headquarters by the guards who took captured deserters to the rear. Soon the Division Officer of the Day came down to the front. I felt so sure that the lines were deserted that I proposed to the Officer of the Day to go forward with a few men and ascertain. He would not consent to my doing it then, but said: “Wait until daylight” This was not far from midnight. About 1 o’clock, as near as I can judge, the rebel gunboats in the river near us began to blow up. Of course the whole line was at once in commotion, and every man was on the qui vive. Long before it was fairly light and before we could distinguish the rebel works in our front, although they were not over 40 or 50 rods away from our vidette line. By order of Captain Leavenworth the vidette or picket line of the Second Brigade moved forward as a skirmish line over the rebel earthworks, and about a mile and a half beyond the works toward the city, encountering; none of the enemy. We then rallied on the centre, which was upon the road I have named, and moved by the flank into Richmond without opposition. The city was then about six miles or six and a half miles distant. The picket line of our division consisted of between three and four hundred men, about one hundred and twenty or thirty of whom, and three officers, were from the Ninth Vermont.

I think we struck the city at what was called Main Street, down near the river. My impression is that there was no street between us and the James. As we entered the suburbs of the city we met a great many citizens. There was great shouting and other expressions of rejoicing at our approach. The city was on fire in our front, down toward the river, and the rebel Government stores were burning and shells were exploding and flying in every direction. We hurried on in the direction of the fire, which seemed to be in our front as we advanced up the street. As we passed along we saw men, both white and black, plundering the deserted houses and stores, but we had no orders to interfere with them at this time. We marched up the street I have spoken of, as far as we could on account of the fire, and then turned at right angles in a northerly direction and marched beyond the northeast corner of the Capitol grounds, as I learned later, where we halted and front faced. We were not in sight of the Capitol grounds at the time, as we were two or three blocks away.

The men were here divided into squads, and I was put into command of one of them. We halted here some little time, and perhaps the Officer of the Day came up, but of this I am not sure. Capt. Leavenworth gave the only commands that I heard or knew anything about, as I now remember. Up to this time we had seen no other Union troops or officers, save those of our division picket force and Gens. Weitzel and Devens, with their staff officers and body guards, and the General who attempted to pass us with a detachment of colored troops. I was directed to march my squad in the direction of the fire and stop the plundering. In my movement toward the fire I marched into the Capitol grounds at their northeast corner, and this was the first time that I had seen these grounds. As we entered the inclosure we encountered the equestrian statue of Washington facing in the direction we were moving and apparently urging us forward. The sight of this figure of the father of our country in this sort of rebellion so affected me for the moment that tears came into my eyes and such a flood of patriotic emotion filled my heart that a brigade of rebels would not have stopped our course at that time.

There were no soldiers, Union or rebel, about the grounds or about the buildings. No flags of any kind, that I saw, were floating from the Capitol. I am positive that we were the first Union troops there. I crossed the Capitol Square over to the west side and took the street down toward the fire and here acted upon my orders, which were to arrest all plunderers and deposit the stolen goods in the Capitol Square. I collected some cartloads, letting the plunderers loose One of our officers was at the same time attempting to put out the fire in the burning building, having procured an old fire engine for the purpose.

An hour or two later, a Lieutenant from the Fifth Maryland Regiment, with a few men, came to me and said that he was ordered to report to me for duty. These were the first Union soldiers, except our troops of the division picket force, that I had seen after getting into the city. He remained on duty with me until the next morning, when he disappeared.

I guarded the stolen stuff for three days, and receiving no new instructions I went to the headquarters of the General in command of our troops, General Devens, I believe, and reported my situation and what I had been doing and asked for instructions. I there found Col. Ed. Ripley Ripley of our regiment but who then commanded the First Brigade. I was instructed to turn the stolen property in my possession over to the owners so far as I could be satisfied of their identity. After doing this, I reported to my regiment, which remained on duty in the city awhile, and then moved over to Manchester, across the James River. While there I received the following order:

“HEADQUARTERS

SECOND BRIGADE, THIRD DIVISION,

TWENTY-FOURTH ARMY CORPS.

May 15, 1865.

“Special Order No. 60.

“II. Lieut. Burnham Cowdrey, Ninth Vermont Volunteers, is hereby detailed for duty in Manchester. Va., and will report to the Captain, H. Q. Sargent, Provost Marshal.

“By command of Col. G. Y. NICHOLS.

“A. M. Heath, Captain Twelfth New Hampshire Volunteers, A.A.A. G.”

I remained on duty under the Provost Marshal until June 16, when the order given below relieved me. While on duly I was stationed at the Virginia Central Railroad depot and had my quarters in the President’s room. Our duties were to preserve the peace. I had charge of that portion of the city and was responsible for good order there. Among other things I [198] was instructed to arrest all persons found selling liquor to our soldiers and to confiscate the liquor. The following is the order referred to above:

“HEADQUARTERS

TWENTY-FOURTH ARMY CORPS,

ARMY OF THE JAMES,

RICHMOND, Va., June 16, 1865.

“Special Order No. 148.

“VI. The commanding officer of the First Division, Twenty-fourth Army Corps, will detail from his command seventy-five (75) enlisted men, properly officered, who will report daily until further orders to Lieutenant H. S. Merrill, A. A. Q, M, at Department Headquarters, to relieve the same number of the Ninth Vermont Volunteers.

“The Ninth Vermont Volunteers, upon being relieved, will report for duty at these headquarters.

‘By Command of Major General John Gibbon.

“(Signed) EDWRD MOALE,

“Assistant Adjutant General”

BURNHAM COWDREY,

Late Captain Company D, Ninth Regiment Vermont Volunteers.

CAPTAIN LEAVENWORTH’S ACCOUNT.

VERMONT STATE NORMAL SCHOOL,

CASTLETON, Vt., Feb. 16, 1893.

Gen. Theodore S. Peck. Adjutant General of Vermont:

Dear Sir—I have been exceedingly interested in the reminiscences of the late Civil War which have been published recently in the Boston Journal, so far as they have come to ray notice. My name having been given as a reference in one of the articles, and a friendly dispute having arisen as to some of the details in relation to the occupancy of Richmond, I am constrained to overcome my repugnance to being made the subject of a dispute wherein all did well as they had opportunity, and none should seek to disparage the part any took in the matter. We were soldiers under orders, and each was ready to obey every known order, even to the giving of his life if necessary. The question at issue is, “What troops first entered Richmond?” The briefest answer is, “The Third Division, Twenty-fourth Army Corps, Major General Charles Devens commanding.” This entry was conducted in an orderly manner. It was not in any sense an unmilitary rush.

In December. 1864, Major General B. F. Butler, commanding the Department of Virginia, reorganized the Army of the James into two corps, called Twenty-fourth and Twenty-fifth respectively. The first consisted of three divisions of white troops under command of Major General Ord; the second consisted of three divisions of colored troops under the command of Major General Godfrey Weitzel. The latter held the line from James River to a point beyond Fort Harrison, where the former took it up and carried it to a point near the New Market Road, as I understand it, connecting with Kautz’s division of cavalry, who carried it back to the James River in the vicinity of Fort Powhatan, the whole forming an ox bow. The latter part of the winter Major General Ord had come into command of the Army of the James, while Major General Gibbons had succeeded to the command of the Twenty-fourth Corps.

During the fall of 1864 I was on duty as Acting Assistant Adjutant General of the United States forces occupying the defences of Bermuda Hundred, under the command of Col. Joseph H. Potter, Twelfth New Hampshire Volunteers, a regular army officer, who soon after received his star. On the reorganization of the Army of the James he was ordered to the command of the Second Brigade. Third Division, Twenty-fourth Army Corps, and I was assigned to duty as his Adjutant General. The work of the winter was very severe, consisting of drills and service on picket line. At 2 o’clock each morning the whole available force was thrown into the breastworks. Col. Potter was a most efficient officer. He was quiet and unassuming in manners, but lull of latent power, and there was little inactivity in his command. The various regiments had suffered during the severity of the campaign of 1864, and had to be reinvested with the sinews of war in anticipation of the opening of the spring campaign that was to end the war. The result was that, before the winter was through, his brigade had been pronounced the best in the corps, and the Ninth Vermont as the best disciplined regiment.

In February Gen. Potter was made Chief of Staff at corps headquarters, and the last of the month I was ordered North to recuperate. Returning the last of March, I took command of my company (K, Ninth Vermont.) April 1, after a separation of nearly two years. Ambitious now to have the best company in the best regiment of the best brigade, as I laughingly told my successor at brigade headquarters, I spent the time in putting my company quarters in as perfect order as the means at my command would permit. On Sunday morning, April 2, I was sent on picket with 135 men of the Ninth Vermont and about 20 men of the Twelfth New Hampshire. There were with me three Lieutenants, two from the Ninth, Joel C. Baker and Burnham Cowdrey, and Lieut. D. W. Bohonon from the Twelfth. The usual brigade guard mount, with which I was familiar under Gen Potter, was omitted, and we were sent directly to-the left of our line, connecting with that of the Twenty-fifth Corps.

I might have stated that Gen. Grant had called to his aid on the left of Petersburg, our army commander. Major General Ord, with two divisions of the Twenty-fourth Army Corps and one division of the Twenty-fifth Corps, the two remaining divisions of the Twenty-fifth Corps extending their line to cover the corps’ front, while to the third division. Twenty [199] fourth Corps, Major General Devens commanding, was accorded the honor of filling the line held previously by the three divisions. We were stretched out with an effort to conceal from the enemy our attenuated line. The Ninth Vermont occupied the quarters of two or more brigades, being very full, while my company took possession of the tents previously occupied by a whole regiment. We made as much show as possible, filling up the tents fronting the enemy, while I had a Colonel’s tent for my use.

Arriving on the picket line, I found Capt. W. M. Kelley. Tenth New Hampshire, on duty as Brigade Officer of the Day, and Lieut. Col. W. W. Bamberger, of the Fifth Maryland Regiment Division Officer of the Day. I was placed in charge of the left of the line, and enjoined to exercise the utmost vigilance. There seemed to be great activity in the rebel works, and we thought they might have learned that half of our forces had been withdrawn. In front of us were Forts Gilmer, Henry and Johnson, mounted with nearly 100 cannon, and they were considered well-nigh impregnable. Capt. Kelley reported himself as feeling too nearly sick to be on duty, and I was glad to relieve him as far as possible The day was spent in keeping an alert watch of the enemy’s line. At about 10 o’clock A. M., the Brigade Commander, Col M. Donohoe, soon after promoted Brigadier General, called upon me, and out of courtesy to the fact that I had been the Adjutant General of his brigade so long, though previous to his taking command, he informed me that a telegram had been received from Gen. Grant directing that our command be held in readiness for an assault upon the works on our front at a moment’s notice from him, should he fail to break their line in his immediate front as he hoped to do. Only a few were made acquainted with this possible movement.

I quietly penciled a letter to my wife, thinking it might be my last message to loved ones at home, though I said nothing of the expected movement, and then addressed myself to the duties in hand. Another call from Gen. Donohoe later in the day brought me information from Gen. Grant that the enemy’s line was yielding to his repeated assaults and that it would not be necessary for us to make an assault.

The enemy kept up a show of strength throughout the day, and there was apparently great activity in their camp as if massing troops. After dark the din of rapid movements was distinctly heard. We were uncertain whether these movements foreboded an attack upon our greatly weakened lines or not. To increase our uncertainty, at midnight the two engineer officers from Mai. Gen. Weitzel’s headquarters called upon me for information as to the contour of our front. I had made such a thorough study of the whole during the day I seemed to have in mind a complete map of it. They desired to select a place suitable for the location of a battery of field guns. I conducted them to a rise of ground with a few scattering trees upon it about fifty yards in advance of our picket line and about the same distance in the rear of our vidette posts. The officers approved the position, and informed me that in an hour a detail of 200 men with picks and shovels would report for duty and would throw up breastworks for a battery to be planted at early dawn to cover an assault either of attack or defence.

I awaited their coming in vain, but at two o’clock a deserter was brought to me, whom one of our videttes had caught. I questioned him and learned that the enemy were evacuating the fortifications on our front. He appeared to be telling the truth, though I was cautious about believing him. I took him to Capt. Kelley, whom I found asleep. I aroused him, told him I had a man claiming to be a deserter, and inquired what disposition I should make of him. He was annoyed at being disturbed, and evidently not wholly awake, and replied, “I don’t care what you do with him.” I then sent him under guard to Gen. Devens. I learn from “Greeley’s Great Conflict,” second volume, that Gen. Weitzel captured a man from the picket line on the Twenty-fifth Corps front, and received from him similar information. This explains the reason of the failure of the fatigue detail to put in an appearance. Soon a staff officer appeared with an order to have our picket force ready for an advance at daylight. The morning was very foggy, but at about half-past 4 the fog lifted from the ground so that we could see to our front. Our anxiety was to be able to pick our way over the line of torpedoes planted in front of the first line of works. The men were eager and it required considerable effort to keep them moving with a steady line. I sent my Lieutenants up and down their front to keep the men in check. At 5 o’clock we had picked our way over these, following the paths trodden by the rebel pickets and guided by the red rags which marked the location of the torpedoes. I understood afterward that only one was exploded, and that only one casualty was reported. As we passed the fort on the right I shuddered at the thought of the probable results had we attempted to take it by storm the previous day. We advanced steadily until our left struck a bend in the James River. The fields of wheat that we passed were a pleasing contrast to the barrenness of our own camps. Only women and children were left in the farm houses we passed, and these informed us that their soldiers were just beyond the woods, and that we “would catch it” when we met them. Not knowing how far in advance their retreating forces were, and being uncertain whether they had left a force behind to oppose pursuit, it seemed prudent to guard against a surprise.

Lieut. Col. Bamberger had received orders from me a greater part of the winter from brigade headquarters and seemed desirous to take counsel with me now. Halting our line at the bend of the river, and noticing that we were three or four miles from camp, where all were hastily preparing for an advance, he proposed a reorganization of his picket force, as he had only 75 men in reserve to supply any vacancies that might occur on the line. He inquired how many men I had from the Ninth Vermont. I replied: “One hundred and thirty-five and two [200] Lieutenants.” He then directed me to take these and throw them out as a skirmish line, and said that he would gather the rest of the picket force under his command as a support to me. Capt. Kelley was standing near, and I asked him if as Brigade Officer of the Day he would claim the right to lead the skirmish line. He replied that he did not care to take the command, that I was acquainted with the men and could, he thought, direct them better than he.

I called my men together, placed Lieutenant Joel C. Baker in command of the right wing and Lieutenant Burnham Cowdrey in charge of the left wing, and deployed the line on either side of what I suppose was the Osborne Pike. We advanced until the pike entered the woods. Reaching it we halted and directed the men to take breakfast while we awaited reports from Major Brooks and Captain Bruce of Gen. Devens’s staff, who had ridden ahead. This must have been between five and six o’clock. Soon an officer of colored troops, accompanied by his Adjutant and less than one hundred colored soldiers in light marching order and fresh from camp, rode up and inquired if the road was clear in front. I replied that I thought it was; that we were awaiting the report of the aforesaid officers, who had ridden on to make a reconnaissance. He demanded to be let through our line and pushed on. I at once gave the order to my line to “rally on the centre,” and said: “Come on, boys, we will see who will lead.” My men had been on duty nearly twenty-four hours, were in heavy marching order, with forty rounds of ammunition and five days’ rations, as when we were sent out it was uncertain about our return. It was my first duty on foot for nearly two years. My breakfast was to have been brought to me from Camp. I had captured a sorry-looking pony and placed upon him a man who seemed unable to walk and handed him my blanket and overcoat.

We overtook the colored troops just as we emerged from the woods. I gave the order to oblique to the right and take the double quick step. The colored lads had a swinging route step and were talking cheerily to each other. As we passed each file, the men would shout to those ahead to “hurry up.” But their demonstrations were so noisy that their officers did not learn of our presence till we turned in ahead. Then their Captain gave them the order to double quick also. For more than a mile we raced it. I became so heated that I tore off my sword-belt and threw it with scabbard and revolver behind me, saying that if there were any that could not keep up they might, if they pleased, bring them along. My dress coat and vest soon followed, collar and necktie followed suit, and my panting breast was bared to the breeze. Soon our colored braves gave up the race and we entered the inner line of defence. Just beyond we came up to the aforesaid officers, who had halted for their men to come up. We were ordered to halt. I repeated the order. It was obeyed to the loss of one or two steps. The commanding officer began to curse us for passing his men, and sent his Adjutant ahead with the order to halt or he would “break” the officer in command. I gave the order to halt that I might hear what he had to say and then passed on. Soon Lieut. Col. Bamberger came up and said: “Captain, are you ready to go home?” I replied, “Yes, if going into Richmond in the lead is a crime.” He then said, “You needn’t halt again.” Soon we came to a small stream, the bridge of which was torn up. We went down through it and up the opposite bank, getting our feet wet. As we passed on, Major General Weitzel, accompanied by his staff, one of whom was Captain Wheeler of Vermont, and his body guard of cavalry, galloped by us. We cheered and he saluted. Soon we came to the Newmarket Road and turned toward Rocket’s. As we drew near to a second-hand store standing at the head of Main Street, a flag was thrust out of the scuttle window. As we saw the Stars and Stripes floating in Richmond our weariness left us for the time, and we went wild with huzzas. My hat went high in the air and I shouted myself hoarse and my comrades were not far behind me in enthusiasm. The scene before us was indescribably grand. “Confusion, confounded” expresses it best. Before us were three lofty bridges, the navy yard and gunboats on fire. Magazine after magazine were being blown up. We turned up the street and halted on “Church Hill” for the rest of our line under the brigade and division Officers of the Day.

A private who had his overcoat belted on came up to me and took it off and threw it around my shoulders, saying: Captain, you will take cold.” Soon my men who fell behind came in, bringing my castaway property. I lost only my rubber blanket. I began to redress, but before I was in presentable shape Major General Devens and staff rode up. Captain Kelley had caught up with us, and, as he said to me, seeing that I was engaged, drew the men up in line and presented arms. General Devens made us a very kind speech, complimenting us for what we had done in leading his advance so well, and directed us to proceed into the city and assist in restoring order and putting out the fires set by the rebel authorities. “All is confusion and disorder,” said he. I again took the lead of my men, Capt. Kelley walking by my side for awhile. About half way up to City Hall, we met a crowd of men, women and children coming to welcome us, bearing two small flags. I took them both, gave one to the man next to me, who placed it in the muzzle of his gun and I waved the other with my sword above my head. The procession consisted of Germans and negros mostly. They kissed the flag I carried, as they begged me to lower it to their reach, and on their knees thanked God for that day, saying, “We have been praying for this day for four years.” None of the buildings on Main Street were then on fire, and the doors and windows were thronged with people. The best description I have ever read is that given by the rebel historian Pollard, an extract from which is given on page 736 of “Greeley’s American Conflict,” Vol. II. As we neared State House Square, I fell exhausted and Captain Kelley passed on up by the State House. It must have been between 7 and 8, as we had [201]

[202] come eight miles. Including stops it must have occupied about three hours.

One old negro brought me a little sherry wine; a negro girl, neatly dressed, gave me a piece of new bread, and I soon revived sufficiently to walk up the hill. A merchant came out of his house to intercede for a guard to protect his goods, saying that he had already been pillaged of $10,000 worth of goods. He claimed to be a son of Connecticut. I asked him for breakfast. He said that his table had been set with untasted food since the day before; they were all too frightened to eat. I asked him to bring me some food to the door, declining to go below for it. A table was set with food for me in the front hall. Having had nothing to eat since the day before, I enjoyed my meal. I then passed to the City Hall, where I found Gen. Ripley in command. The Third Division had entered the city. While taking my meal I saw them pass. The people were amazed at the sight of well fed men and animals, and well equipped troops in comparison with those which had just evacuated the City. Gen. Ripley was busy furnishing guards to frightened citizens of the captured city. As I entered the hall, the wife of Commissioner Oulds, well knowing the bad odor in which her husband was because of his treatment of Union prisoners, was pleading for a guard, fearing she might be made to suffer because of her husband’s acts. She was a pleasant mannered lady. The General turned to me and directed me to furnish her a guard. She insisted that his instructions be in writing. I was bidden to write them out, and instructed the guard to permit no person to enter or pass out of the house during the next twenty-four hours.

The men were directed to be placed on guard at the State House and other public buildings that had escaped the flames, while I was directed to patrol the city. All the officers and men were by Gen. Devens’s orders put to work to stop the conflagration that had destroyed thirty blocks of buildings. During the night I was directed to search business places in the unburned districts, to ascertain if any liquors could be found. We found that the Mayor’s work the night before had been well done. Only empty barrels and kegs were found.

Tuesday I assisted Wm. Ira Smith, one of the proprietors of the Richmond Whig, to obtain a permit to issue his paper, and a half sheet was printed late in the day. Soon after noon I received permission to relieve my men who were on guard in different parts of the city. The last detail found consisted of a Sergeant with his men, who were guarding the State House. As we came out of the grounds President Lincoln passed up the street by us, leading his little son “Tad,” and followed by a rapidly increasing crowd of negroes who were shouting, “Father Abraham has come!” with other enthusiastic exclamations. We had been on duty nearly three days and two nights with scarcely any rest. I asked the Sergeant if he would like to go and see the President. He replied that he was too tired and wished to get to camp as soon as possible. I replied that I would go with him, as I would probably have another opportunity to see the President. Little did we know what ten days would disclose!

Returning to camp I again took command of my company. The regiment was seeking a new camp and that night rested with blankets and the ground only for beds, and the sky for a covering. The next morning, Wednesday, we laid out our new camp and began to pitch our tents. While thus engaged an orderly rode up and handed me an order from Major General Weitzel, commanding the United States forces in and about Richmond, appointing me Assistant Provost Marshal, and directing me to report at once to the Provost Marshal General, General John Coughlin, who placed me in charge of his principal office in the United States Custom House, which had been used as their Treasury Building by the Confederate Government. I was made his “assistant and confidential associate.” For the next month this office was a busy place. Many branch offices were established under competent officers. We soon had “Libby Prison” and “Castle Thunder” filled with a new class of occupants. Stolen property had to be hunted up and restored to the rightful owners, business permits to be granted, the hungry to be fed, and order brought out of dire confusion.

It was my privilege to rescue many important papers and documents of the rebel Government and later to turn them over to Major Curtis who was sent down from Washington to take charge of them. Later I secured an incomplete file of Richmond newspapers, extending from 1861 to 1865. These are now bound and may be found in the Vermont State Library with several volumes of other important rebel documents. The latter part of April General Patrick, Provost Marshal General of the Army of the Potomac, relieved General Coughlin. At his request I remained with him a week to assist his staff in becoming acquainted with the workings of the office, when I was appointed by Major General Ord Assistant Adjutant General to General Coughlin, commanding the district of the Appomattox, embracing seven counties lying between the Appomattox and James Rivers.

June 13, 1865, I was mustered out of service with my regiment at Richmond, Va.

By an examination of the foregoing statement it will be found that Capt. Kelley was Brigade Officer of the Day, In command of the picket line of the Second Brigade, and that, as he and Lieut. Prescott both say, the whole division picket line advanced as a skirmish line, under orders from division headquarters, which was represented by Major Brooks and Capt. Bruce. After we crossed the first line of intrenchments these officers went on in advance, and were not seen by us again. Being unsupported from camp, the Division Officer of the Day reorganized his line for better protection and to secure a more orderly advance. The Ninth Vermont was much the largest in the division, and probably one-third of the whole picket force was from this regiment. This was probably the reason why Col. Bamberger selected this detail for the skirmish line he wished to establish. There were three officers with it and greater unity [203] would be secured than if he had made a selection from the different regiments. Besides, time was saved, and the whole matter was arranged without delay, and within ten minutes my new line was deployed and advanced. Lieutenant Prescott, being on the extreme right, may not have received the order to consolidate the line and may have continued the advance with the few men with him.

I would not question a word of his statement. He may have passed up the Newmarket road a mile or so to our right. Thanks to the brave fighting of half of our two corps and the Army of the Potomac at the left of Petersburgh, our entrance to Richmond was a bloodless one. We expected opposition, but did not find it. There was nothing to hinder anyone from entering Richmond, either alone or in company with others.

Your report as Adjutant General of Vermont was taken from the State roster and was intended merely to show the part Vermont troops took in the war, and was not intended to detract from the service of the troops from other States. The claim was not that no one else went in ahead of the skirmish line organized as stated above, but that it was “the first organized body of troops to enter the rebel capital.” This fact gave it precedence in the line of organized troops, but no precedence in the honor in which every officer and man of God. Devens’s division shared equally. That a holocaust of lives was not required by us should be a cause of gratitude. We should have made the sacrifice without a murmur, had it been required of us.

ABEL E. LEAVENWORTH,

Late Captain Ninth Vermont Infantry.

- Details

- Categories:: Other Sources After 1865 Battery Defenses Fort Harrison/Chaffin’s Farm Capitol Square City Hall White House of the Confederacy Railroads Rocketts Confederate Evacuation of Richmond Union Occupation of Richmond Lincoln's Visit to Richmond Alcohol Crime & Mayhem Fires Monuments and Memorialization Race Relations Deserters Free Negroes Unionists and Spies Castle Thunder Libby Prison Customs House

- Published: 19 November 2017